As Europe is witnessing continual increase in numbers of immigrants coming from the Middle East and Northern Africa, it is also facing an unprecedented support to far-right political parties among all European states.The rise of far-right parties is probably most visible in Nordic states, Austria, Great Britain and in particular France where Marie Le Pen received 25% of votes for her Front National during European Parliament elections in 2014 and thus become successful alongside with Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party or the Freedom Party of Austria. However, Nordic states appears to be a hub of this rise where members of the far-right parties got into government and as the immigration crisis continues, they are the biggest competitors of the major traditional parties.

Author: Kateřina Lišaníková, master student of Security and Strategic Studies at the Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk university.

Numbers of asylum seekers nearly doubled

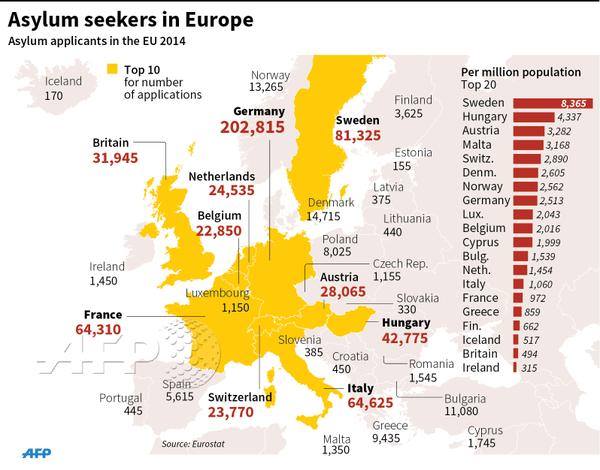

Denmark and Sweden have the richest welfare system for asylum seekers which makes these two countries frequently sought by immigrants. Despite the fact that the number of Swedish inhabitants is nearly the same as e.g. in the Czech Republic, asylum in this Nordic country was granted to more than 33,000 refugees in 2014. Compared to Germany, whereas in Sweden 77% of applicants were granted protection at their first attempt, Germany accepted only 45 % of them. Moreover, there are other differences between these two countries – while Sweden had to deal with more than 81,410 asylum seekers cases last year, Germany had to go through more than 247,635 requests which represents the greatest number within all EU members. Even the UK is way behind with 29,340 cases. Despite the huge number of asylum requests in Germany, Sweden seems still to remain a preferred place for immigrants due to the percentage of granted asylums and the numbers of incoming immigrants to original inhabitants as well. For example, numbers of Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Sweden have grown up to the point where even Swedes got the impression they should start to learn Arabic as well.

Denmark is after Sweden the second most popular Nordic country among immigrants. Although it does not reach Sweden’s statistics data, the interesting thing is that the number of asylum seekers coming to Denmark nearly doubled in 2014 (14,815) compared to the previous year (7,557). It can be expected that 2015 will reach another record. On the other hand, it needs to be noted that Denmark has got so called opt-out on EU’s Justice and Home Affairs which means it is not part of refugees redistributive plan. Therefore, it will probably not reach such a high number of asylum seekers as e.g. Sweden.

There is no surprise that alongside the increase in immigrants there is also a correlation with the increase in support of far-right parties. These political subjects are well-known for their nationalistic ethos and strong anti-immigration rhetoric. The most significant support was registered particularly among the Sweden Democrats and the Danish People’s Party.

Go Sweden Democrats!

Probably the most controversial far-right party is the Sweden Democrats as their roots lie within neo-Nazi movements from 1990s. However, its new leader Jimmie Åkesson tries to unchain the party from this unpopular history, creates a brand new party with traditional values and steps down from any extremism. Experts agree that this is not a classical extremist party due to its political programme and behaviour which do not fit to the standard pattern. Nonetheless, there is no secret that it can be grateful for their success to its anti-immigrant rhetoric. In 2006, Sweden Democrats gained 3% in the general elections which was not enough to get any seats in the Parliament. Elections in 2010 finally granted them the access to Riksdag with 5,7% of votes. However, major success came in 2014 when the party was able to get significant 12,9% which made it the third biggest party in the Parliament and what’s more, it seems that their popularity grows with every month. After a coalition crisis in December 2014 when Prime Minister Stefan Löfven announced early elections for this year, the latest polls registered support to the Sweden Democrats from 14,7% up to 19,5% (Social Democrats which is currently the leader party in Riksdag can count with 25,9%). Their success may have two reasons. First of all, as the only parliamentary party within Nordic countries it has not been a part of any government coalition which would make their voters angry. Secondly, it is the only party in the Parliament with a strong anti-immigration rhetoric. Its TV commercial was even banned during the pre-election campaign. Moreover, as Malmö has faced 30 bomb attacks since January 2015 and Stockholm is seen as one of the most dangerous cities to live in Europe, there is no surprise it enjoys such support. The current situation is boosted up with the fact that by the end of June the county Kalmar in southern Sweden announced that refugees would get free bus passes to ensure the increase in mobility and integration within migrant community. This initiative is worth 58,691 dollars per year and whereas it was warmly welcomed by immigrants, it provoked the opposite reaction within Swedish population.

Dannish advert to deter immigrants

Although the Danish People’s Party also receives a significant support within Denmark, Danish government is much more open to changes in their immigration policy than their Swedish neighbour. Danish politicians for example condemned Swedish decision to forbid Sweden Democrats‘ TV spot by saying that it was clear censorship. Moreover, not only the Danish People’s Party uses the increasing number of immigrants as a political issue. Current Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen from the centre-right Liberal Party (Venstre), has several times stressed out that Denmark needs to reduce these numbers which rises quite quickly (from 556 asylum seekers in April and 723 in May last year to 879 in May this year). Danish ministers surprised even more as they announced that unemployment welfare benefits introduced by the previous government would be significantly lower to make Denmark less attractive to immigrants.

However, the Danish People’s Party proposed to send refugees back to their country of origin according to Australian model (Sweden Democrats were willing even to pay refugees to make them leave). The party also wants the government to launch a video campaign in foreign media to discourage immigrants thinking about seeking asylum in Denmark. Not surprisingly, the idea has immediately become a target for criticism as being ‘un-Danish’. Nevertheless, the step represented just a reaction to recent ‘discovery’ of FRONTEX agency that posted an information sheet whose distribution was launched by smugglers for refugees purposes to simply pick the most suitable European country for them based on terms of stay.

Thus as a result of increasing immigration, rich welfare system and several attacks (e.g. in February when a Palestinian immigrant shot two people dead and wounded five police officers in front of synagogue) changed Danish centre-left government into the centre-right one during elections in June 2015. Once again, after elections in Norway in 2013 when the rise of far-right parties had started, and a massive success of the Sweden Democrats, the Danish People’s Party has proven the phenomena continues. In 2011, Venstre won elections with 24,8% followed by Social Democrats with 24,8% and the Danish People’s Party with only 12,3%. Nowadays the winner of elections 2015 became Social Democrats with 26,3% followed by the Danish People’s Party with 21,2% and very closely Venstre with 19,5%. As it can be seen, the far-right party growth is more than significant. It is worth noting that Finnish second largest government party is the Finns Party and Norwegian Progress Party is the third largest one, both are far-right as well.

Is there any security threat?

The main question remains if we should consider the rise of these far-right parties a security threat to the democratic system in each country or more widely, in whole Nordic region. It probably depends on the point of view. According to Dr Anders Sannerstedt, a political scientist at Lund University, the Sweden Democrats does not fulfil all assumptions to be perceived as far-right party with neo-Nazi roots. There still might be some members who act inappropriately by posting racist comments on the Internet or painting swastika on the walls, however, these people are immediately expelled from the party or quit voluntarily as Åkesson has zero tolerance policy to previous neo-Nazi roots. Moreover, there are also other mechanisms to prevent far-right or far-left parties to step into the Parliament. The so called Militant democracy was firstly mentioned by Karl Lowenstein in 1937, but the first state which adopted the concept was Germany after the Second World War to prevent any rise of extremism. The idea is that democracy defends itself by forward mechanisms to block and punish any anti-democratic ideas and acts. That can be done by tools such as law-sanctions, institutional (by creating institutions to combat extremism) or discursive (by argument way) mechanisms (1).

For example, Sweden provides defence against extremism by Section 8 of its Criminal Code:

„A person who, in a disseminated statement or communication, threatens or expresses contempt for a national, ethnic or other such group of persons with allusion to race, colour, national or ethnic origin or religious belief shall, be sentenced for agitation against a national or ethnic group to imprisonment for at most two years or, if the crime is petty, to a fine.“

And in Chapter 29, section 2, paragraph 7 by adding what aggravation circumstances for the court are:

„Whether a motive for the crime was to aggrieve a person, ethnic group or some other similar group of people by reason of race, colour, national or ethnic origin, religious belief or other similar circumstance.“

Speaking of Sweden as well as Denmark, the laws against hate speech which are widely used and open discussion, may be also taken into account.

Therefore, it can be concluded that if current so called far-right parties which remain in the Nordic parliaments, were contravening basic democratic principles, the states would have tools how to ban their activities. The reason why they are hot topic primarily in Denmark and Sweden are opposite stands of the public: one side claims these parties are racist and do not support open society; and the other supports them because in its opinion, they are the only parties who actually try to solve the immigration problem as they see the situation worsening and if countries do not adopt any counter measures, the Nordic society and culture as such will be in a great danger. For example, the Finns Party after revealing its election programme triggered a great discussion whether the party does not exceed the democratic borders as some of the statements against immigration included offensive expressions.

However, to avoid greater tensions within inhibitants, it is probably best to stick with the Finnish consensus view among main parliament parties that says: „it is preferable to have populists on board rather than allow them to gain ground in opposition“ (which is now happening in Sweden as the Sweden Democrats are not part of either, the Coalition nor Alliance and getting stronger).

Additional sources:

Mareš, M. – Výborný, Š. (2013): Militantní demokracie ve střední Evropě. Brno: centrum pro studiumdemokracie a kultury. 249 s.

Backes, U. (2007): Meaning and Forms of Political Extremism, Central European Political Science Review, Vol. IX, No. 4, pp. 242-262.

Loewenstein, K. (1937): Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, I. The American Political Science Review, Vol. 31, No. 3., pp. 417-432.