In recent years, the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah has significantly expanded its operating environment. Hezbollah’s criminal networks are spread almost worldwide, generating hundreds of millions of dollars in illegal profits to fund its operations. That is why Hezbollah is currently considered the wealthiest terrorist group globally, with an annual income of 1.1 billion USD in 2018 [1]. Hezbollah engages in criminal activities with the active or forced support of the Lebanese Shiite diaspora in Europe, Africa, and North and South America. The Islamist organization has reconsidered its business model from primarily state funding, backed by Iran, and diversifies its financial activities into drug, arms, and money laundering. Part of the profits from these illegal activities is transferred to Hezbollah in Lebanon, where they are used to fund social, religious, and educational services, armed and political activities within the Shiite community in southern Lebanon.

A substantial part of Hezbollah’s criminal activities occurs in the European Union, especially in Germany and France. Due to the growing number of sympathizers of the Shiite organization, Berlin designates Hezbollah entirely as a terrorist organization (both military and political wing) since April 2020. Therefore, the author will focus in the following text on a case study of Hezbollah’s activities in the Federal Republic of Germany and the government’s response to these activities.

General overview

The Lebanese Hezbollah movement (“Party of God” in Arabic) is often referred to by the research community as a hybrid player – it represents a political party, social welfare organization, an international terrorist organization, an international organized crime group, and a militia that is larger and more powerful than the entire Lebanese army. Hezbollah uses terrorist tactics and other forms of violence and coercion to achieve its goals but seeks to present itself as a legitimate political party [2].

The birth of Hezbollah is usually dated to 1982 in connection primarily with the fifteen-year-long Lebanese civil war or in response to the Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon. However, it has been essential to see its germs since the 1970s, connected with its multiannual development and the Iranian revolution of 1979, which later had a significant impact on the movement [3]. The organization enshrined its ideology in a manifesto in which Hezbollah pledged to expel Western powers from Lebanon, called for the destruction of the state of Israel, and pledged allegiance to Iran’s top leader. Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah has headed Hezbollah since 1992 [4].

In the following years, thanks to the massive material and financial support of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the „Party of God“ developed into one of the most potent militias throughout the region with a rocket arsenal of 130,000 explosive devices [5]. During this period, the movement built a large stronghold in the Bekaa Valley and the southern districts of Beirut [6]. It also strives to radicalize Muslims in Europe through its TV channel „Al-Manar.“ It supports the Palestinian Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, classified by the EU as terrorist organizations [7].

Background and development of Hezbollah’s presence in Germany

Hezbollah confronts the German government with a security and foreign policy dilemma for more than 30 years. On the one hand, the Iran-dependent group is a political and social actor and is again involved in the Lebanese government. On the other hand, the „Party of God“ is held responsible for terrorist attacks and assassinations in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, as well as responsible for other subversive actions such as kidnappings [8].

In general, many authors and think tanks [9] [10] [11] agree that Germany has over time become a major centre of Hezbollah’s European activities. The first signs of the presence of its sympathizers appear in Germany as early as the 1980s within the massive exodus of many Shiite Lebanese from the war-torn country [12]. In the 1990s, the group’s operational potential in Western Europe, including Germany, increased significantly. Hezbollah followers have committed several acts of violence with at least 130 murdered civilians or kidnapped almost 100 Western hostages, including German ones [13] [14].

In particular, in Germany since the unification of the republic in 1990, security officials have drawn attention for years to the presence of a Lebanese Islamist group, which began to show terrorist traits [15]. Hezbollah’s activities in Germany were associated primarily with the character of Imad Mughniyeh, the group’s military chief and coordinator for foreign affairs, often referred to as Hezbollah’s No. 2 man. He was closely connected to Iran and Western countries, including Germany, and was responsible for planning, preparing, and carrying out terrorist operations [16].

The first significant milestone in Hezbollah’s activities in Germany was the 1989 bombing of Israeli targets, which confirmed local authorities‘ concerns about establishing a Hezbollah cell on German soil, but still of unknown proportions [17]. In 1994, German intelligence services warned of a Mughniyeh-led Hezbollah unit infiltrating Germany to attack US targets [18]. According to Ranstorp [19], these members of the foreign operations group included Hussein Khalil, Ibrahim Aqil, Muhammad Haydar, Kharib Nasser, and Abd al-Hamadi.

The presence of Hezbollah members operating on German territory has grown steadily, as evidenced by the specific numbers identified in the annual reports of the local secret services. In 2005, there were 800 members or sympathizers of Hezbollah in Germany, while in 2008, there were already 900. In that year, Hezbollah was the second-largest Arab Islamist group, whose members were established there [20]. In the same year, a German court first deported a citizen who was an active member of Hezbollah. He was accused „only“ of supporting international terrorism – membership in the organization at that time was still wholly legal [21].

In February 2007, the Federal Minister of the Interior declared that the 900 Hezbollah supporters known to the security authorities would meet in 30 cultural and mosque associations in Germany [22]. Over the following years, German intelligence services repeatedly pointed out Hezbollah’s efforts to recruit suicide bombers in Germany. In 2013, an annual report from the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution showed that 950 members of Hezbollah operated in Germany, 250 of them in the capital Berlin. Authorities have also begun to uncover the background to funding German Hezbollah operatives who have raised funds from Islamic charities based in Germany [23]. The most famous example was the Orphan Project Lebanon („Waisenkinderprojekt Libanon e.V.“), which was managed by the Lebanese Al-Shahid Foundation (Martyrs‘ Foundation). The Orphan Project Lebanon was banned by the Federal Ministry in 2014 [24]. Both organizations promote suicide killings, and there is no doubt that they were closely linked to Hezbollah [25].

In 2019, the number of Hezbollah members in Germany rose to 1,050 [26]. A weighty turning point came in April 2020, when Germany’s Interior Minister announced that „any association with or public expression of support for Hezbollah was banned immediately“ [27]. Despite the ban, Hezbollah continued to maintain its activities in Germany, especially in mosques and community groups. There has also been no major organizational restructuring [28]. According to intelligence reports, members of Hezbollah „maintain organizational and ideological cohesion, among other things, in local mosque associations, which are primarily financed by donations“ [29]. Although the AIJAC report [30] registered a noticeable decline in Hezbollah’s public support in Germany over the past two years, the latest German security report shows that the number of Hezbollah members rose to 1250 in 2021. In Lower Saxony, Hezbollah’s base reached a high (but closer unspecified) number and was identified as a security threat to the local constitutional and democratic system [31].

The kinds of modus operandi of Hezbollah’s activities in Germany

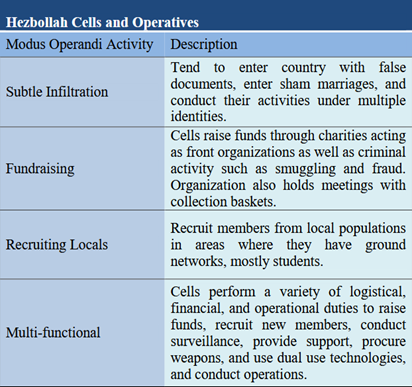

Jasmine Williams provides a detailed analysis of the activities of Hezbollah members in Germany in her study „Hezbollah’s Threat in Germany: An Updated Overview of its Presence and the German Response.“ The analysis distinguishes four basic types of modus operandi of Hezbollah in the territory of this European state – Hezbollah advances its interests through subtle infiltration, recruiting German locals, fundraising, and multifunctional operations. The types mentioned below are presented in more detail in the table. The analytical framework is inspired by Levitt’s study [32], which examined the general modus operandi of terrorist groups.

Subtle Infiltration

The infiltration of Hezbollah members into German territory was already partially reflected in the previous subchapter. The exact numbers of people expanding Hezbollah’s membership base in Germany from the outside are not precisely quantified in all efforts, or these values belong to classified information by the German intelligence services.

Hezbollah members in Germany are primarily closely affiliated with mosque associations in Germany, funded by donations and member fees. There are approximately 30 such public benefit associations in Germany [33]. According to some German intelligence reports, the German Hezbollah network has links with well-known institutions such as the Islamic Center Hamburg (IZH), the Imam Reza Mosque in Berlin, the Imam Mahdi Center in Münster, or the Al Mustafa Community in Bremen. It should be noted that direct links with these institutions have only been publicly demonstrated in a small number of cases [34] [35].

Infiltration is also closely linked to the public presence and spread of Hezbollah propaganda in Germany. The main activity in this regard is the organization of various demonstration events, thanks to which the number of Hezbollah supporters is growing. The most important event of a similar type is the so-called “Al-Quds Day March,” which occurs every year in Berlin [36]. The Al-Quds march is a kind of show of power by the Shiite Islamists in Germany. On this day, Iranians loyal to the regime and Hezbollah members go public with their slogans in Germany and advertise the destruction of Israel on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm. On Quds Day, the marchers propagate the teachings of Ayatollah Khomeini, extol the Islamic dictatorship in Iran, and promote the claims to extend the rule of Islam beyond Iran. The central slogans of the Quds March in Tehran to this day are „Death to Israel, Death to the USA!“ [37]. For instance, the Ministry of the Interior estimates up to 1,100 mainly young Hezbollah supporters taking part in this event in 2012 [38].

Another essential tool of Islamist propaganda of Hezbollah in Germany is the Al-Manar television station, mentioned in the introduction. According to the Federal Government, this TV channel „uses a cleverly prepared hate speech propaganda against members of the Jewish faith and the State of Israel.“ The station was banned as unconstitutional in Germany so that Al-Manar cannot be broadcast in public spaces. Nevertheless, it can still be received via the internet [39].

Recruiting German locals

Due to Hezbollah’s growing popularity and public response and its Shiite Islamism among young Muslims, the recruitment of local citizens has become another suitable tool to expand Hezbollah’s activities in Germany. As early as 2007, German security authorities stated that recruitment to the organization occurred mainly in the Internet environment, where young German members of Hezbollah are firmly connected, including social media and various web forums [40].

Over the years, several cases of recruiting German citizens to carry out illegal actions on behalf of Hezbollah have been proven. The case of the German convert Steven Smyrek is most famous in public. Hezbollah sent him to Lebanon to train weapons and explosives and then commissioned him to find possible attack sites in Israel. However, in November 1997, he was arrested by Israeli security agencies at Ben Gurion Airport. His goal was probably to carry out a suicide attack in Tel Aviv or Haifa [41]. In 2008, medical student Khaled Kashkoush, who was arrested in Israel, was recruited and paid by Hezbollah to recruit Arab-Israeli students in Germany. After that, he was supposed to find a job in an Israeli hospital to collect information about security agents or soldiers being treated there [42].

Fundraising

„Party of God“ members raise funds in Germany in two main ways – by charitable donations and by criminal activity.

Charitable donations

The features of charitable fundraising have already been discussed – these are very sophisticated and difficult-to-detect financial channels. Hezbollah uses its affiliated mosque associations and raises funds within the framework of religious ceremonies and membership contributions [43] [44].

Probably the most famous charity linked to Hezbollah was, as already stated, the Orphans Project Lebanon, whose assets were frozen and closed in 2014. During its existence (2007 to 2013), it has raised 3.3 million euros across various federal states, with a member base had up to 80 people [45]. In 2016, the case of the Refugee Club Impulse in Germany, which requested 100,000 euros from the Berlin Cultural Education Project Fund, collapsed publicly. This organization was allegedly led by the co-organizers of the Al-Quds demonstration [46].

One recent case shows that the threat of financing a terrorist group through a charity-based strategy will not stop. In May 2021, Germany’s Interior Ministry has outlawed three organizations accused of collecting money for Hezbollah – German Lebanese Family, People for Peace, and Give Peace. As in previous cases, these non-profit associations collected donations for „martyr families“ in Lebanon. After banning these organizations, large-scale raids took place across seven federal states [47].

Criminal activity

To this day, Hezbollah in Germany can rely on several criminal networks. These revenues form Hezbollah’s indispensable financial basis, with the help of which it can finance its terrorist and military activities in Lebanon and war activities against Israel. Hezbollah’s criminal activities have increased significantly over the past decade. In doing so, the organization wants to make itself more independent of funding from Iran, which was experiencing financial difficulties due to international sanctions [48].

Hezbollah’s criminal activities in Germany mainly include money laundering, arms, and drug trafficking. The „economic department“ of Hezbollah reports to the military wing (the „Jihad Council“), which is further evidence that the political, terrorist, and economic wings are inseparable [49].

In February 2016, joint investigations by US and European authorities uncovered Hezbollah’s criminal structures. During the investigation, known as „Operation Cedar,“ 15 people were arrested from the Hezbollah criminal business network, including four people from Germany. This network washed at least 75 million euros between 2014 and 2016, the proceeds of which were to benefit Hezbollah in Lebanon [50]. The proceeds from the sale of large quantities of cocaine smuggled into Europe were transferred to Lebanon via Germany. The drug money was invested in vehicles and luxury watches that were exported to Lebanon and redeemed there. This money was used to finance new deliveries of cocaine from Colombia [51] [52].

The structures discovered during Operation Cedar are probably just the tip of the iceberg. The criminal machinations of Hezbollah in Germany seem to be established much earlier. As early as 2010, Der Spiegel reported that the Rhineland-Palatinate LKA (State Criminal Police Office) arrested four Lebanese people at Frankfurt Airport who had more than 8 million euros in cash with them. The members of an extended Lebanese family from the Speyer area had probably passed millions on profits from drug trafficking in Lebanon to Hezbollah for years [53].

Multifunctional operations

In general, Hezbollah seems to use the Federal Republic as a logistics centre, which it also uses for many multifunctional operations. In this respect, it is mainly the purchase of weapons, operational salaries, administrative overheads, logistics, and any reconstruction and development of infrastructure. Hezbollah engages in cooperation between agents or groups of different organizations for operational, logistical, or financial associations and has become a point of contact for terrorists operating outside their home base in their respective diaspora [54] [55].

In the post-2000 period, there was no terrorist act in Germany directly related to Hezbollah members or other affiliated organizations. The last such incident dates back to 1992 when three Iranian-Kurdish politicians in exile were murdered in a Berlin restaurant. The killings were visibly ordered by the Iranian regime [56].

Conclusion

This analysis confirmed the premise that the Lebanese Shiite organization Hezbollah has long been a threat to Israel in the Middle East region and, in addition, has the ability to operate secretly in developed Western countries. A German case study has shown that Hezbollah’s hidden networks, which have been undercover across the Federal Republic for more than 30 years, are seriously a cause for concern for the domestic security apparatus. Although there have been no more severe terrorist incidents on German territory in the 21st century caused by Hezbollah supporters, the „Party of God“ base of over 1,200 active members poses a serious risk to Germany’s internal security. Even though these supporters of Hezbollah use Germany primarily as a retreat, logistics space, and for raising money intended for its members and families in Lebanon. Still, terrorist acts by infiltrated or locally radicalized Hezbollah members against Israeli or Western targets cannot be ruled out.

Although the German government has enforced various countermeasures to combat Hezbollah’s illegal activities over the years, the Islamist organization has exploited its vulnerabilities in many cases. A relatively recent decision to ban the activities of the entire movement on German soil and to label Hezbollah with all its wings as a terrorist organization seems to be a crucial tool in the fight against Hezbollah. The consequence of this decision on the continuation of Hezbollah’s activities in Germany is likely to become apparent later, as the collection and analysis of monitoring and information on such hidden networks of terrorist groups will take a long time. The question, therefore, arises as to whether Hezbollah will continue to act on German territory and whether money laundering and other acts of financing will be carried out. Nonetheless, it is feared that support structures will shift to those EU member states that have not yet taken any measures to ban Hezbollah entirely.

Bibliography

[1] Soliman, Renz. 2021. “5 Richest Terrorist Groups In The World: ISIS Is Only Top 5“. International Business Times, 9th August 2021 (https://www.ibtimes.com/5-richest-terrorist-groups-world-isis-only-top-5-3269391?utm_source=iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2704307_).

[2] Azani, Eitan. 2011. Hezbollah: The Story of the Party of God. From Revolution to Institutionalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[3] Azani, Eitan. 2011. Hezbollah: The Story of the Party of God. From Revolution to Institutionalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 48.

[4] Daniel, Jan. 2014. „Vládnutí nestátních ozbrojených aktérů v selhávajících státech: Případ Hizballáhu.“ Mezinárodní vztahy Vol. 49, No.2, 32–51. (in Czech)

[5] ELNET. 2021. “Hisbollah – Eine wachsende Gefahr für Europa

und den Nahen Osten“. European Leadership Network, April 2021 (https://elnet-deutschland.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Report-Strasbourg-Forum-I.pdf). (in German)

[6] Leemhuis, Remko. 2019. “Hezbollah in Germany and Europe“. The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy, November 2019 (https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/ISPSW_657_Leemhuis.pdf).

[7] EFD. 2009. „Hisbollah’s Spendensammelverein in Deutschland“. European Foundation for Democracy, June 2009 (https://docplayer.org/15772017-Hisbollah-s-spendensammelverein-in-deutschland.html). (in German)

[8] EFD. 2009. „Hisbollah’s Spendensammelverein in Deutschland“. European Foundation for Democracy, June 2009 (https://docplayer.org/15772017-Hisbollah-s-spendensammelverein-in-deutschland.html). (in German)

[9] Williams, Jasmine. 2014. „Hezbollah’s Threat in Germany: An Updated Overview of its Presence and the German Response“. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Spring 2014 (http://www.ict.org.il/UserFiles/Williams%20-%20Hezbollah%20in%20Germany.pdf).

[10] AJC Berlin Ramer Institute. 2019. „DIE HISBOLLAH IN DEUTSCHLAND UND EUROPA“. American Jewish Committee Berlin Ramer Institute, October 2019 (https://ajcgermany.org/system/files/document/AJC%20Berlin_Hisbollah%20Broschuere_DE_0.pdf). (in German)

[11] Leemhuis, Remko. 2019. “Hezbollah in Germany and Europe“. The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy, November 2019 (https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/ISPSW_657_Leemhuis.pdf).

[12] Phillips, James A. 2007. Hezbollah’s Terrorist Threat to the European Union. Washington: Heritage Foundation,

[13] Ranstorp, Magnus. 1997. Hizb ́Allah in Lebanon. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

[14] EFD. 2009. „Hisbollah’s Spendensammelverein in Deutschland“. European Foundation for Democracy, June 2009 (https://docplayer.org/15772017-Hisbollah-s-spendensammelverein-in-deutschland.html). (in German)

[15] Levitt, Matthew. 2013a.“Hezbollah’s Organized Criminal Enterprises in Europe.“ Perspectives on Terrorism, 7, no. 4, 27–40 (https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2013/issue-4/hezbollah%E2%80%99s-organized-criminal-enterprises-in-europe–matthew-levitt.pdf).

[16] Burgos, Marcelo Martinez and Alberto Nisman. 2006. German government reports referenced in Argentina, Buenos Aries, Investigations Unit of the Office of the Attorney General. Office of Criminal Investigations: AMIA Case.

[17] Levitt, Matthew. 2013a.“Hezbollah’s Organized Criminal Enterprises in Europe.“ Perspectives on Terrorism, 7, no. 4, 27–40 (https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2013/issue-4/hezbollah%E2%80%99s-organized-criminal-enterprises-in-europe–matthew-levitt.pdf).

[18] Burgos, Marcelo Martinez and Alberto Nisman. 2006. German government reports referenced in Argentina, Buenos Aries, Investigations Unit of the Office of the Attorney General. Office of Criminal Investigations: AMIA Case.

[19] Ranstorp, Magnus. 1994. „Hizbollah’s command leadership: Its structure, decision‐making and relationship with Iranian clergy and institution“. Terrorism and Political Violence 3, vol. 6. 303–339 (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09546559408427263).

[20] BfV (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution). 2005. Annual Report of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution 2005. Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, BfV.

[21] Agence France-Presse. 2005. „Lebanese Hezbollah Official Forced to Leave Germany.“ Agence France-Presse, 5th January 2005.

[22] EFD. 2009. „Hisbollah’s Spendensammelverein in Deutschland“. European Foundation for Democracy, June 2009 (https://docplayer.org/15772017-Hisbollah-s-spendensammelverein-in-deutschland.html). (in German)

[23] Weinthal, Benjamin. 2013. “German mosque groups raising funds for Hezbollah“. Jerusalem Post, 23rd June 2013 (https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/german-mosque-groups-raising-funds-for-hezbollah-317500).

[24] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[25] EFD. 2009. „Hisbollah’s Spendensammelverein in Deutschland“. European Foundation for Democracy, June 2009 (https://docplayer.org/15772017-Hisbollah-s-spendensammelverein-in-deutschland.html). (in German)

[26] BfV (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution). 2018. Verfassungsschutzbericht 2018. Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, BfV (https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/download/vsbericht-2018.pdf) (in German)

[27] AIJAC. 2021. „Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee of Intelligence and Security’s Review into the Re-Listing of Hizballah External Security Organisation – Additional evidence provided on notice „. Australia/Israel Jewish Affairs Council, July 2021 (https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:ESwx-cNVDhMJ:https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx%3Fid%3Dc1b4c2eb-f167-4996-bc1e-f8adb7d6c410%26subId%3D707342+&cd=1&hl=cs&ct=clnk&gl=cz&client=firefox-b-d).

[28] AIJAC. 2021. „Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee of Intelligence and Security’s Review into the Re-Listing of Hizballah External Security Organisation – Additional evidence provided on notice „. Australia/Israel Jewish Affairs Council, July 2021 (https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:ESwx-cNVDhMJ:https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx%3Fid%3Dc1b4c2eb-f167-4996-bc1e-f8adb7d6c410%26subId%3D707342+&cd=1&hl=cs&ct=clnk&gl=cz&client=firefox-b-d).

[29] Weinthal, Benjamin. 2021. “Germany sees increase of Hezbollah

supporters and members – intel”. The Jerusalem Post, 5th June 2021 (https://www.jpost.com/international/germany-sees-increase-of-hezbollah-supporters-and-members-intel-670092).

[30] AIJAC. 2021. „Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee of Intelligence and Security’s Review into the Re-Listing of Hizballah External Security Organisation – Additional evidence provided on notice „. Australia/Israel Jewish Affairs Council, July 2021 (https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:ESwx-cNVDhMJ:https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx%3Fid%3Dc1b4c2eb-f167-4996-bc1e-f8adb7d6c410%26subId%3D707342+&cd=1&hl=cs&ct=clnk&gl=cz&client=firefox-b-d).

[31] Weinthal, Benjamin. 2021. “Germany sees increase of Hezbollah

supporters and members – intel”. The Jerusalem Post, 5th June 2021 (https://www.jpost.com/international/germany-sees-increase-of-hezbollah-supporters-and-members-intel-670092).

[32] Levitt, Matthew. 2003. Hezbollah: „A Case Study of Global Reach“. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, September 2003 (https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/ACLURM001616.pdf).

[33] BfV (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution). 2014.: “Presseinformation: Verbot des Vereins ‘Waisenkinderprojekt Libanon e. V.’” Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, BfV (https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/presse/pi-20140408-wkp-verbot). (in German)

[34] Bild. 2018. “Polizeipräsident trifft Hisbollah-nahe Gruppe”. Bild, 7th December,

2018 (https://www.bild.de/politik/inland/politik-inland/terrornetzwerk-muensters-polizeipraesident-trifft-hisbollah-nahe-gruppe-

58863536.bild.html) (in German)

[35] Leemhuis, Remko. 2019. “Hezbollah in Germany and Europe“. The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy, November 2019 (https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/ISPSW_657_Leemhuis.pdf).

[36] Williams, Jasmine. 2014. „Hezbollah’s Threat in Germany: An Updated Overview of its Presence and the German Response“. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Spring 2014 (http://www.ict.org.il/UserFiles/Williams%20-%20Hezbollah%20in%20Germany.pdf).

[37] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[38] Weinthal, Benjamin. 2013. “German mosque groups raising funds for Hezbollah“. Jerusalem Post, 23rd June 2013 (https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/german-mosque-groups-raising-funds-for-hezbollah-317500).

[39] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[40] Phillips, James A. 2007. Hezbollah’s Terrorist Threat to the European Union. Washington: Heritage Foundation,

[41] Levitt, Matthew. 2013b. Hezbollah. The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

[42] Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2018. “Arrest of Hezbollah agent from Kalansua”. MFA.GOV.IL, 6th August 2018 (https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/terrorism/hizbullah/pages/arrest%20of%20hizbullah%20agent%20from%20kalansua%206-

aug-2008.aspx)

[43] Weinthal, Benjamin. 2013. “German mosque groups raising funds for Hezbollah“. Jerusalem Post, 23rd June 2013 (https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/german-mosque-groups-raising-funds-for-hezbollah-317500).

[44] BfV (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution). 2014.: “Presseinformation: Verbot des Vereins ‘Waisenkinderprojekt Libanon e. V.’” Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, BfV (https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/presse/pi-20140408-wkp-verbot). (in German)

[45] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[46] Leemhuis, Remko. 2019. “Hezbollah in Germany and Europe“. The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy, November 2019 (https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/ISPSW_657_Leemhuis.pdf).

[47] DW (Deutsche Welle). 2021. “Germany carries out raids on Hezbollah-linked groups“. Deutsche Welle, 19th May 2021 (https://www.dw.com/en/germany-carries-out-raids-on-hezbollah-linked-groups/a-57576748).

[48] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[49] Levitt, Matthew. 2018. “Hezbollah’s Criminal and Terrorist Operations in Europe” AJC.org, 2nd September 2018 (https://www.ajc.org/news/hezbollahs-criminal-and-terrorist-operations-in-europe).

[50] Spiegel. 2016. “Libanesen sollen im Auftrag der Hisbollah mindestens 75 Millionen Euro Drogengeld in Europa gewaschen haben“. Der Spiegel, 30th April 2016. (http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/vorab/libanesen-sollen-im-auftrag-der-hisbollah-mindestens-75-millionen-euro-drogengeld-in-europa-gewaschen-haben-a-1089981.html). (in German)

[51] MFFB. 2019. “10 Gründe für ein Verbot der Hisbollah.“ Mideast Freedom Forum Berlin, November 2019 (https://www.mideastfreedomforum.org/fileadmin/editors_de/Artikel/Policy_Paper/Mideast_Freedom_Forum_Berlin_-_10_Gruende_fuer_ein_Verbot_der_Hisbollah.pdf). (in German)

[52] Shay, Shaul. 2019. “The terror threat of Iran and Hezbollah in Europe”. Research Institute for European and American Studies, January 2019 (http://www.rieas.gr/images/middleeast/rieaspub19.pdf).

[53] Ulrich, Andreas. 2010. “Koks für den Terror”. Spiegel, 11th January, 2010 (https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-68621892.html).

[54] Levitt, Matthew. 2013a.“Hezbollah’s Organized Criminal Enterprises in Europe.“ Perspectives on Terrorism, 7, no. 4, 27–40 (https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2013/issue-4/hezbollah%E2%80%99s-organized-criminal-enterprises-in-europe–matthew-levitt.pdf).

[55] Williams, Jasmine. 2014. „Hezbollah’s Threat in Germany: An Updated Overview of its Presence and the German Response“. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Spring 2014 (http://www.ict.org.il/UserFiles/Williams%20-%20Hezbollah%20in%20Germany.pdf).

[56] Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. 2014. „Murder at Mykonos: Anatomy of a Political Assassination.“ Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, 1st January 2014.